In economics and politics, few acronyms are thrown around as frequently as GDP. Whether in headlines, government briefings, or international comparisons, GDP is treated as the go-to measure for economic health and national performance. But what exactly is GDP, what does it tell us, and where does it fall short?

In this guide, we’ll explore the basics of GDP, how it’s used, why it matters, and when it might mislead. We’ll also look at alternative ways to measure the well-being and performance of a country beyond simple economic output.

What Does GDP Stand For?

GDP, or Gross Domestic Product, represents the total monetary value of all final goods and services produced within a country’s borders during a specific period, usually a year or a quarter.

GDP measures economic activity, not necessarily economic well-being. It answers the question: How much value is being produced in this economy right now?

There are three primary approaches to calculating GDP:

- Production Approach: Adds up the value added at each stage of production.

- Income Approach: Totals all incomes earned (wages, rents, profits).

- Expenditure Approach: The most common, using the formula: GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

Where:- C = Consumption

- I = Investment

- G = Government Spending

- (X – M) = Net Exports (Exports – Imports)

Why Do Governments and Economists Use GDP?

GDP is one of the most widely used economic indicators for a few key reasons:

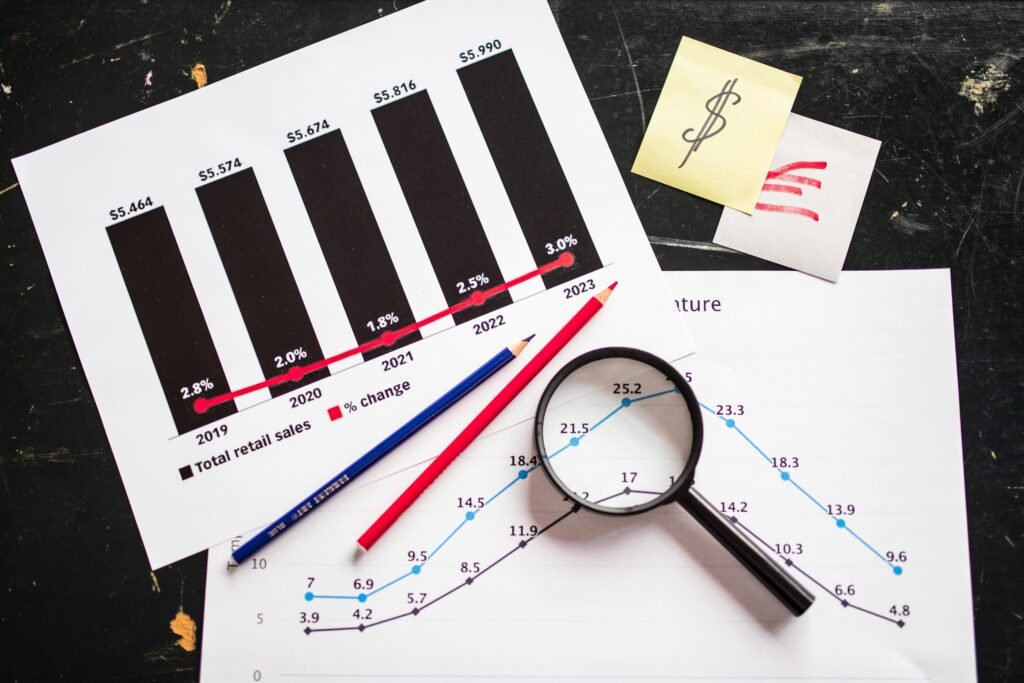

1. Economic Growth Tracking

GDP lets policymakers and economists monitor whether an economy is growing or shrinking. Increases in GDP typically suggest economic expansion, while decreases signal contraction or recession.

2. Comparing Countries

GDP is commonly used to compare the economic output of different countries. While GDP in absolute terms can be misleading (large countries naturally produce more), GDP per capita—which divides total GDP by the population—is a better measure of economic productivity per person.

3. Budget and Policy Planning

Governments use GDP figures to assess fiscal health, budget planning, and set monetary policy. Central banks often base interest rate decisions on GDP trends.

4. Debt Analysis

The famous Debt-to-GDP ratio is used to evaluate a country’s ability to manage and repay public debt. A country with high debt but high GDP may still be financially stable.

GDP: Advantages as a Metric

GDP remains a central economic indicator for good reason:

- Simplicity: It condenses complex economic activity into a single figure.

- Comparability: Standardized calculations allow for global comparisons.

- Data Availability: Nearly every country publishes GDP data regularly.

- Correlation with Employment and Investment: Generally, as GDP grows, so do jobs and private investment.

GDP: The Downsides and Limitations

Despite its popularity, GDP has several limitations that can distort the real picture of an economy.

1. Ignores Income Inequality

GDP can grow even if the wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few. A rising GDP doesn’t mean the average citizen is better off. Countries with high GDP but severe inequality (e.g., some oil-rich nations) illustrate this flaw.

2. No Insight into Environmental Impact

GDP counts all production as positive, regardless of environmental damage. For example, if a country cuts down its forests to export timber, GDP rises—even if long-term ecological damage occurs.

3. Doesn’t Value Unpaid Work

Childcare, eldercare, and volunteering aren’t counted in GDP because no money changes hands—even though these activities are crucial to societal well-being.

4. Short-Term Focus

GDP incentivizes short-term growth, sometimes at the expense of sustainability or human development.

5. Used for Political Spin

Politicians may cherry-pick GDP figures to make their policies look successful. A minor increase can be hailed as a “booming economy” even when the broader population is struggling.

GDP and Public Debt: A Misleading Metric?

One of the most common misuses of GDP is in the calculation of debt sustainability. The Debt-to-GDP ratio is used by rating agencies and governments to judge if a country is borrowing responsibly. But this can be misleading:

- GDP can fluctuate, especially during recessions, making debt appear worse than it is.

- It doesn’t measure government revenue—which actually pays for debt service.

- Countries with low GDP but high tax capacity may be better off than those with higher GDP and poor fiscal management.

For instance, during COVID-19, GDP dropped sharply across many countries, which inflated their debt-to-GDP ratios—even though their actual ability to repay debt hadn’t changed significantly.

Better Alternatives to GDP

Given its shortcomings, economists and policymakers have begun to consider complementary or alternative measures to GDP.

1. HDI – Human Development Index

Developed by the UN, HDI combines life expectancy, education level, and income per capita. It focuses more on human well-being than pure output.

2. GPI – Genuine Progress Indicator

GPI adjusts GDP by accounting for pollution, income inequality, crime, and unpaid labor. It gives a more holistic view of social progress.

3. Happiness Index / World Happiness Report

This measure ranks countries by self-reported life satisfaction, freedom, social support, and corruption levels. It shifts the focus from what economies produce to how people feel about their lives.

4. Green GDP

This metric deducts the cost of environmental degradation and resource depletion from standard GDP. It’s rarely used officially but increasingly discussed.

5. Wealth Per Capita (Inclusive Wealth Index)

This approach measures not just income, but natural capital, human capital, and manufactured capital. It aims to evaluate whether growth is sustainable.

Should We Stop Using GDP?

Despite its flaws, GDP is unlikely to disappear anytime soon. Its global acceptance, standardized methodology, and regular reporting make it indispensable for macroeconomic analysis. But there’s growing consensus that GDP should not be the only metric.

Instead, it should be used in tandem with other indicators—like inequality indices, environmental data, and well-being metrics—to provide a balanced scorecard of national performance.

In fact, organizations like the OECD and World Bank now encourage the use of multi-dimensional approaches to assessing prosperity.

Conclusion

GDP is a powerful but imperfect tool. While it remains the gold standard for measuring economic output, it doesn’t capture the full story of a nation’s health, happiness, or sustainability. It’s essential to understand both what GDP tells us—and what it doesn’t.

By incorporating complementary indicators like the Human Development Index, Green GDP, and subjective well-being surveys, we can paint a more accurate and compassionate picture of global progress.

For policymakers, business leaders, and engaged citizens alike, the real goal should not just be more growth, but better growth.

Need a professional website to grow your business across the EU?

👉 Rakuzan.eu provides digital business solutions tailored for entrepreneurs — website development, optimization, and more.

Launching your online presence? Make sure your hosting is fast and reliable.

👉 Use Hostinger to get started quickly and affordably.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, tax, or investment advice. Readers should consult with a licensed professional before making any financial or business decisions.